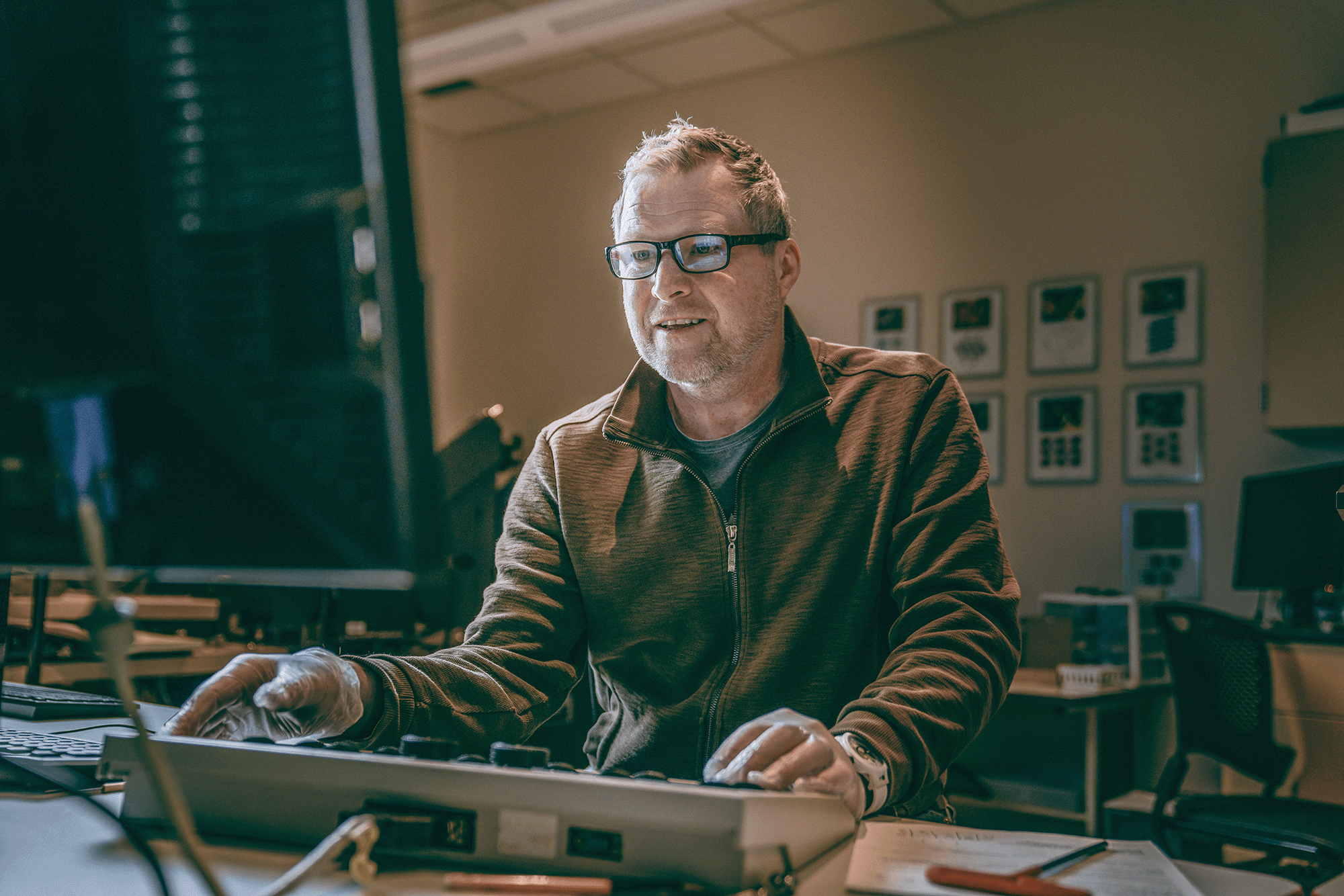

Jim Karner has trekked almost annually to Antarctica on expeditions looking for meteorites. The research associate professor in the Department of Geology and Geophysics has probably seen and handled more cosmic debris than most will see in a lifetime. But on the morning of August 13, 2022, he—along with the rest of the northern Wasatch Front—heard one explode, for the first time.

“That was really loud,” he remembers thinking as he stood in his driveway. “My immediate thought was, ‘Wow, that sounds like what people have described as meteorites exploding and breaking the sound barrier.’ ”

Within days, a piece of what would eventually be named the Great Salt Lake meteorite made its way into Karner’s hands, giving him and the U an opportunity to learn what secrets of space this chunk of rock brought with it to the Salt Lake Valley.

Searching in Antarctica

Karner’s expertise in meteorites comes from years of expeditions to Antarctica as part of the NASA-funded ANSMET, the Antarctic Search for Meteorites. Since 1976, ANSMET has sent expeditions, including a few select volunteers such as Karner, to pick up meteorites off the ice during the Antarctic summer. The samples are classified and curated by NASA Johnson Space Center and the Smithsonian Institution for analysis by planetary scientists who can’t just walk up to a planetary body or asteroid and chip off a sample whenever they need one.

Meteorites don’t fall any more often at the poles than they do anywhere else on the planet. But those that fall in Antarctica can be caught up in the continent’s glaciers—conveyor belts of ice that carry rocks and dirt from the center of Antarctica toward its coasts. In some places, these glaciers run up against mountains before reaching the coasts, dumping their rocky cargo, including meteorites. Those specimens, protected from weathering, could have landed on Earth anytime in the last two million years.

The first requirement for any prospective volunteer meteorite hunter is to send a letter to ANSMET, explaining their interest in the program.

“This letter is the first test,” Karner says. “You have to put something down on paper and actually mail it.” Prospective applicants have to show that they’re up for the challenge. “Can you handle the cold? Can your family handle you being gone for two months?”

In 2004, Karner wrote his letter and embarked on his first expedition.

“I remember the first meteorite we found,” Karner says. He was in a group of four, slowly patrolling the ice on snowmobiles. “One of the women on the team gave the sign that she’d found one,” he says. It was a rare type, a stony-iron meteorite, that he’s only seen again three times.

“I think humans have a tendency to collect and search for things, because of the thrill that comes with the hunt and finding something special,” he says. “My first trip was awesome that way. I still get excited to hunt meteorites.” Karner kept going back and became the co-principal investigator of ANSMET in 2016.

Four-time veteran ANSMET volunteer Jani Radebaugh remembers the first meteorite she saw on the ice. The group was gathering around a dark object. “I looked down and there was this big rock sitting on the ground,” says Radebaugh, a professor of geological sciences at Brigham Young University. “And I thought, ‘Wait, we don’t have to dig for these? It’s just sitting there on the ground.’ I was absolutely floored.”

While she loved the experience, it wasn’t always easy. “It’s every bit as hard as—probably harder than—I expected, to live in a tent in Antarctica for six weeks,” she says. “You’ve gotta dress like an astronaut when you go out there. Not quite like an astronaut, but it takes you 20 minutes to get dressed. It felt like the closest thing to outer space operations on earth that I could imagine.”

Karner adds that the solitude is otherworldly. “When we’re out there in the mountains of Antarctica, it’s just rocks, ice, and snow—and that’s it,” Karner says. “There’s no bugs, there’s no trees, there’s no leaves. Once the snowmobiles are all turned off, it’s super quiet.”

Searching the Playa

After the boom on that August morning, Karner contacted a friend at NASA Johnson Space Center, Marc Fries, who had developed methods for tracking where meteorites land using Doppler radar. Fries sent Karner a map of the potential impact area, on the southwest shores of the Great Salt Lake near Stansbury Park.

“Jim called me and said, ‘Do you wanna go look for a meteorite?’ ” Radebaugh recalls. They set out searching—this time without parkas and snowmobiles. “It’s white expanses, just like Antarctica,” she says. “So we felt right at home, except we were on foot.”

Any fragment of dark rock, they noticed, would be seen from far off. “So I was thinking, ‘Yeah, we’re gonna find something,’ ” Karner adds.

Except someone already had. Meteorite enthusiasts pay close attention to any reported fireball and also use public record Doppler data to zero in on potential impact sites.

“They are there in the next few days from all over the country,” Karner says. Within 30 minutes of starting their search, Karner got a message from Fries: Sonny Clary, a private meteorite hunter from Las Vegas searching in the same area, had found something.

Clary, sporting camo gear, a wide-brimmed hat, and a metal detector strapped to his four-wheeler, met up with Karner and Radebaugh. He let them examine the sample.

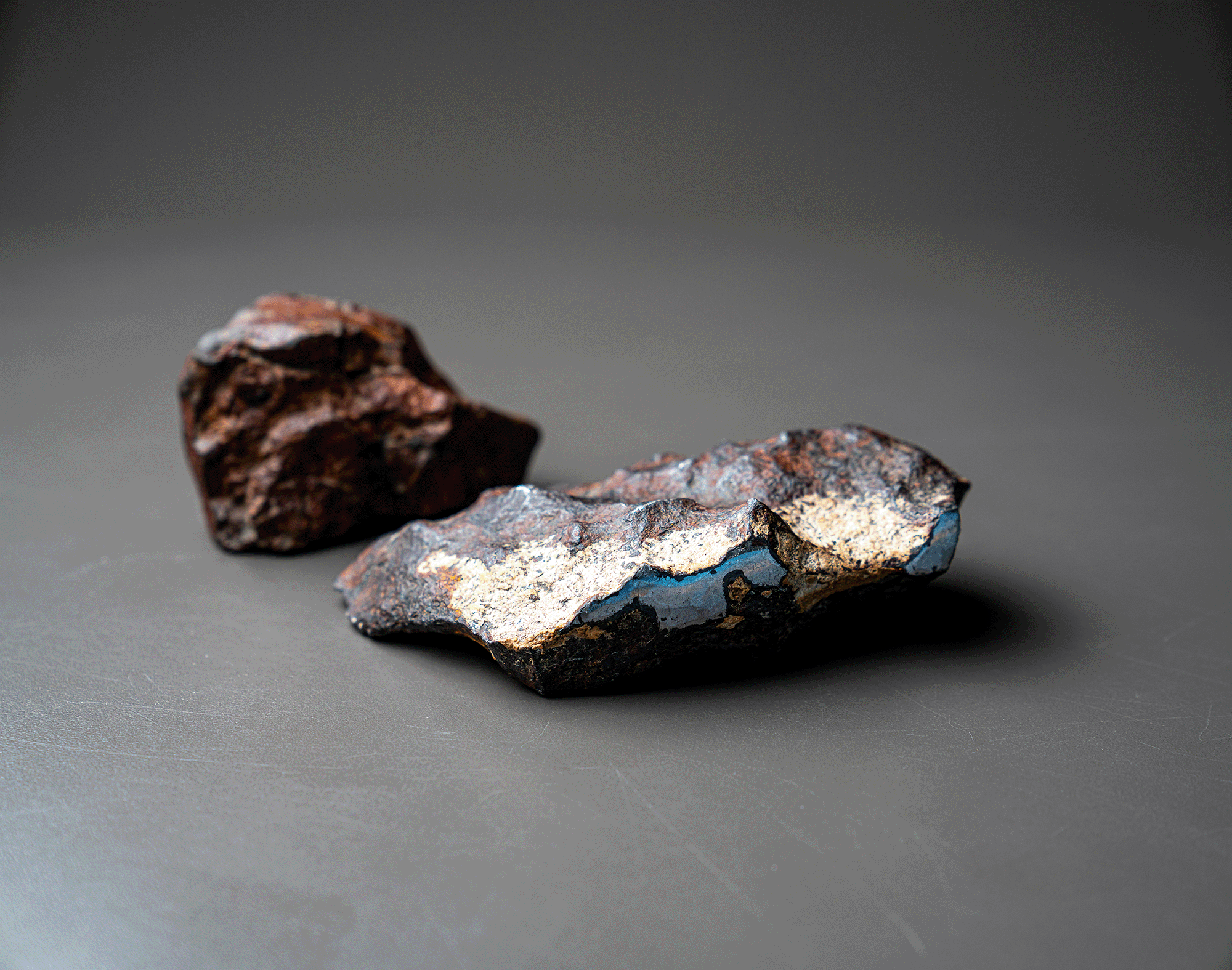

“The piece was beautiful,” Radebaugh says, “fist-sized or larger.”

They discussed where Clary might donate a piece of it for analysis. The Meteoritical Society, which issues official names for meteorites, requires that at least 20 grams or 20 percent of a found object is donated to a scientific institution for analysis before it can be named. After bandying around schools with extensive planetary science programs or schools closer to Clary’s home, the group agreed that the sample would be analyzed at the U.

What We Can Learn from Meteorites

Meteorites tell their story through their composition. Some are made of almost pure iron, suggesting that they come from the core of an asteroid. Some consist of rock fragments, indicative of a parent asteroid’s violent past. Still others are constituted of round chondrules—little drops of rock that date back to the very beginning of the solar system.

To learn about the composition of this meteorite, Karner brought the sample to the U’s electron microprobe lab, led by Sarah Lambart, assistant professor of geology and geophysics.

It was her first time working with a meteorite.

“It’s not every day that I can analyze a sample that was ‘floating’ in space just a couple of weeks earlier,” she says.

The classification came back as an “ordinary chondrite,” which is a common type, but Karner says the fact that the fireball was seen by so many people adds to its scientific value.

“They can probably trace its origins back to the asteroid belt,” he notes, “and its orbital path around the sun. And that hasn’t been done with a lot of meteorites.” Researchers may also be interested in the booms heard as it fell, and in determining how big the original rock was before it burned up in the atmosphere.

“I think it’ll be of great interest to not only scientists,” he adds, “but to the general public as well.”

Before Karner sent off the sample to the Cascadia Meteorite Laboratory at Portland State University (the U is not an official repository for meteorite specimens), he had the chance to suggest a name. In December, he got word that the name was official: The Great Salt Lake meteorite. Karner had classified and named a meteorite from New Mexico before, but this was different.

“I was kind of tickled,” he says.

About the author: Paul Gabrielsen is a science writer for the U’s Genetic Science Learning Center.

Does anyone know if the 2 people who found the meteorite near Delta in 1944 were connected with or imprisoned at the Topaz Japanese Internment camp there from 1942 to 1945?

I found an article about this. https://geology.utah.gov/map-pub/survey-notes/glad-you-asked/glad-you-asked-what-is-utahs-largest-meteorite/

Akio Ujihara, of West Los Angeles, and Yoshio Nishimoto, of Stockton, California, found the meteorite on or before September 24, 1944, while rockhounding for chalcedony for a lesson at the Topaz Lapidary School.

Wow, what an incredible story! Reading about Jim Karner’s expeditions to Antarctica in search of meteorites and his recent experience with the Great Salt Lake meteorite was truly fascinating.

It’s amazing to think that there are chunks of space rock right here on Earth that hold secrets about our universe and its history. The fact that these meteorites can be preserved in the glaciers of Antarctica for such long periods is mind-blowing. It shows how important and valuable these expeditions are for scientific research.

I was also intrigued by the process of becoming a volunteer meteorite hunter for ANSMET. Writing a letter and being willing to endure the extreme conditions of Antarctica certainly shows the dedication and passion of these researchers. The thrill of the hunt and the joy of finding something unique must be an incredibly rewarding experience.

The discovery of the Great Salt Lake meteorite, and the subsequent analysis of its composition, will undoubtedly provide valuable insights into the origins of our solar system. Learning about its orbital path and potential origins from the asteroid belt will deepen our understanding of celestial bodies and their movements.

I applaud the collaborative effort among scientists, meteorite enthusiasts like Sonny Clary, and institutions like the U and the Cascadia Meteorite Laboratory. Their work not only contributes to scientific knowledge but also sparks curiosity and interest among the general public.

Thank you for sharing this incredible story of exploration and discovery. It reminds us that there is so much we have yet to learn about the universe, and these dedicated individuals are helping us unravel its mysteries piece by piece.