About three milliliters of liquid and a syringe. That’s all there seemingly is to the COVID-19 vaccines. But the years of scientific development and centuries of research that helped scientists arrive at this moment tell a much broader story. From the time a worldwide outbreak of the novel coronavirus was recognized in early 2020, scientists and medical experts have worked urgently to create vaccines capable of slowing and stopping the virus’ spread. And the fact that not just one but several COVID-19 vaccines have been invented and distributed is an immense feat—a testament to human cooperation.

“One of the reasons we have so many vaccines in the U.S. is that the government subsidized the different companies and vaccine platforms to maximize the likelihood of success,” says Sankar Swaminathan, an infectious disease physician at the U. “Medical corporations, doctors, federal and state governments, and more all came together to create safe and effective immunizations.”

The total number of lives saved by vaccines is incalculable and spans generations. We no longer have to fear being crippled by polio. We can safeguard ourselves against tetanus. Every fall, flu shots help us stave off winter sickness. Measles, mumps, and chicken pox don’t have to be a regular part of childhood. Vaccination has either virtually eradicated these diseases or provided protection against them, turning ailments of decades past into memories.

"A particular scientific experiment in rural 18th-century England set the stage for the emergence of uncountable amounts of life-saving medicine."

Now COVID-19 is our newest opponent. But even in this moment, with so much hanging on the promise of remarkable scientific discovery, misunderstandings and misinformation about vaccines can run as rampant as any virus. For some, whether to get vaccinated at all is a hot-button issue. According to a Pew Research Center survey in late 2020, about 40 percent of Americans said they probably or definitely wouldn’t get a coronavirus vaccine if made available to them. Overturning that fear and mistrust is a tall order, but there is a way to do so, says Nadja Durbach, a U professor of history who wrote the book on vaccines—literally. It’s called Bodily Matters, and it describes how vaccines were developed and the anti-vaccination movement that followed.

Part of what makes vaccines so potent is the way our bodies naturally cope with disease. “Cultures all over the planet have independently come to realize how exposure to a mild or similar illness can shield us from deadlier ones,” says Durbach. “And a particular scientific experiment in rural 18th-century England set the stage for the emergence of uncountable amounts of life-saving medicine.”

OFF THE BOVINE

Do you know what the word “vaccine” means? Even before the pandemic, parents had to consider vaccinations for their children, and anyone looking to travel abroad was often recommended MMR, flu, and tetanus shots. But the etymology of the word doesn’t have anything to do with needles. Vaccine has its root in the Latin word vacca—“cow.”

We pay homage to cows every time we get an inoculation thanks to English physician Edward Jenner. “During his time, no one really knew what viruses were. Jenner was working decades before the germ theory of disease—that microorganisms, or germs, cause illness—became understood and accepted,” says Durbach. Doctors could see that people got sick, and they developed treatments for those ailments, but the basic mechanics of what diseases truly are and how they spread was unknown.

“This was an era during which terrible diseases like cholera and even the Black Death were thought to have been caused by miasmas or ‘bad air’ that came from the rot and decay of organic matter,” notes Durbach.

This doesn’t mean that doctors were totally in the dark. During his rounds, Jenner heard that dairymaids who caught cowpox didn’t catch smallpox, which caused a terrible fever, rashes, and a steep death toll. With that in mind, Jenner set about an experiment. What if exposure to one less-lethal illness could make you resistant to a similar, deadlier disease? To find out, in 1796 Jenner scraped matter from the cowpox lesions of dairy-maid Sarah Nelms and inoculated 8-year-old James Phipps.

“This wasn’t like vaccination today,” says Durbach. Inoculation involved taking matter from a diseased person and creating a small cut or wound on an uninfected person's arm or leg to introduce the disease-carrying tissue into. That’s what Jenner did in his experiment. Two months later, after Phipps recovered, Jenner injected the child with smallpox—and the boy did not get sick. In honor of the cow’s contribution to medical history, the word vaccine was born.

People have been trying different methods of inoculation for centuries. In the 1600s, Chinese Emperor K’ang Hsi had his children inoculated against the same disease by having smallpox scabs ground up and blown into the children’s nostrils. Doctors in Ethiopia, India, Turkey, and elsewhere developed their own methods of inoculation, as well, which inspired western doctors.

Methods have changed quite a bit since even Jenner’s time. Medical ethics boards wouldn’t allow anything like Jenner’s casual experiment today, says Durbach, and we get injections by needle instead of being cut with lancets. But the underlying, basic science is still the same.

"Vaccines can help us save countless lives.

We just have to choose to let them."

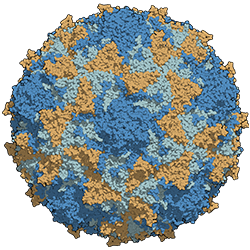

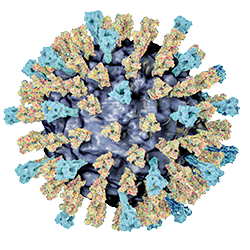

By introducing a small amount of dead virus or the prompt for creating proper antibodies into ourselves, our immune systems are stimulated to respond. A vaccine doesn’t cause the disease but creates an immune response in which antibodies and cells specific to that disease are created—a kind of bodily memory so that if we come into contact with the virus, we already have antibodies specific to the pathogen, says Swaminathan. Some vaccines will prevent you from getting sick if you come into contact with the virus but might not completely stop the spread of the virus to other people. The COVID-19, rotavirus, whooping cough, and other vaccines may not provide sterilizing immunity —meaning viruses or bacteria may still replicate inside your body—but the immunizations can reduce transmission, he says.

Essentially, vaccines are a human-made way to help what our bodies naturally do when they encounter diseases. Vaccines only work because our bodies already have the ability to “remember” particular viruses and mount a specific response. In the case of the new COVID-19 vaccines, Swaminathan says, “They do have different mechanisms, but ultimately they all present the body with spike protein, eliciting an immune response.”

A MATTER OF TRUST

After Jenner described his experiments in 1798, other doctors began to try his methods of inoculation against smallpox. The method worked. Within a few years, vaccination was becoming more popular in England and other European countries. Finally, there was a way to fight against the scourge of smallpox that had killed so many.

But the professionalization and spread of vaccination wasn’t always welcomed by the public. Smallpox vaccination became compulsory in 19th-century England. Social class impacted how people complied with state-mandated vaccination. “The rich could buy themselves out of vaccinations or afford doctors who inoculated patients with small incisions,” says Durbach. Poorer classes, however, were often required to be vaccinated by government doctors who made multiple cuts in babies’ arms, evoking claims of mutilation. Mistrust built, with many people feeling like they were being forced to endure a torturous procedure in the name of “public health.”

“The resistance to vaccination originally was twofold,” she says. In treating smallpox, people were wary of putting cowpox scrapings—an animal product—into their bodies. The second concern was government mandates. Some felt that the government was telling them that they had to endure a risky procedure, while the more affluent could get access to better treatment or avoid it if they wished. “The original anti-vaccination movement was highly political,” centering on a distrust of both the science and the government, says Durbach.

INOCULATING AGAINST FEAR

Similar concerns exist in some communities today, says cancer researcher Deanna Kepka, an associate professor of nursing. Her area of expertise is the human papillomavirus, or HPV, a very common sexually transmitted infection that can lead to different cancers. The disease can be prevented by a vaccine, but, as with others, there’s some resistance to vaccination.

“I think there’s anxiety around what we put into our bodies,” Kepka says. To someone who might not have heard of HPV or who is unaware of how vaccines work, she notes, “understanding which invisible substances can cause our bodies harm and which are protective is complicated.”

And misinformation about vaccines in general has run rampant in the past, confusing the issue. For example, a debunked 1998 study falsely suggested vaccines can cause autism. These discredited findings have led to outbreaks of whooping cough and measles, despite these diseases having previously been largely under control.

“The science is abundantly clear, and vaccines are both safe and life-saving,” Kepka says. But this issue isn’t about science alone. Facets of race, class, and even political affiliation can affect how people respond to being vaccinated. In a 2018 experimental study of 2,500 people to see how hypothetical case counts of a disease in their community would affect their willingness to be vaccinated, Juliet Carlisle, associate professor of political science, and her colleagues found that people with conservative political views were more likely to shun vaccination than others on different parts of the political spectrum.

That isn’t to say that everyone opposed to or unsure about vaccinations fits into one category—racially, politically, or otherwise. And there are fears built off injustices practiced against underrepresented communities, says Durbach. For example, in the Tuskegee syphilis study, hundreds of African American men were denied treatment and deliberately misled so doctors working with the U.S. Public Health Service could study the natural course of syphilis in the Black population.

“While many are mistrustful of government, in our other related work we’ve found that trust in primary care physicians is very high,” Carlisle says. “There’s an opportunity there for people to have conversations with their doctors and put any doubts to rest. Family doctors can play a big role in positively impacting vaccination rates.”

Even what a virus makes us think of by association can complicate matters. “HPV is complicated because of the relationship to sexual behavior,” Kepka says, as there can be a sense that vaccinations will encourage young people to take more risks and be more sexually active. Even though this isn’t the case, and the vaccine truly is protective, the urge to protect children and maintain their innocence leads some to distrust and/or avoid the medicine.

The rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines is another case in point. Current mistrust can have more to do with unequal access to medical care in underserved communities than the vaccine itself, Kepka says. This makes it all the more important to not only educate but to work closely with community partners and advocates. “We need alliances with community health workers centered around persistence, patience, consistency, and not being negative or critical,” Kepka says. “Talking with community members is key to building trust and understanding barriers.”

People might be wary of vaccination for an entire host of reasons. To overcome that, Durbach says, “We should focus on why people feel targeted or disenfranchised or frightened and think about the ways in which class and race shape people’s experience of their bodies and the government.”

Part of what will build trust is the success of the vaccines themselves, says U infectious disease specialist Andy Pavia. In the case of COVID-19, virus cases in Utah and around the country are falling as the vaccines reach people. “I’ve been really pleased that the FDA has done a spectacular job of being transparent, of waiting until the data were pretty complete before reviewing it. And to make sure that outside experts had a voice, people who had no commercial ties, no political ties whatsoever,” Pavia says. “Hundreds of vaccine experts have been poring over these data and coming to the same conclusion—that the vaccines work and that they’re safe.”

“Pause for a moment to consider how remarkable that is—that after one year, effective and safe vaccines are going out to people all over the world,” Pavia adds. Getting a vaccination isn’t just a wonder of medical research encapsulated in a shot. All the research and testing that goes into each vaccine has another half—your own body.

Vaccines are not a standalone fix but a prompt that brings our bodies into action to defend ourselves against disease. “Vaccines are a form of preparation, of safeguarding the people we care about by safeguarding our own bodies," Pavia says. "Vaccines can help us save countless lives. We just have to choose to let them.”

About the author: Riley Black is a Salt Lake City-based freelance writer.

Vaccines' Greatest Hits

From just 1995 to 2015, the CDC estimates that vaccines prevented some 750,000 deaths and 322 million illnesses, saving more than $1.38 trillion in health care costs. And according to a study from UNICEF, vaccines prevent the deaths of 3 million children worldwide each year. These are only a few of many diseases that have been kept in check, or virtually eradicated, thanks to vaccines.

POLIO

POLIO

Jonas Salk famously invented the first polio vaccine in 1955. In severe cases, polio can cause paralysis; it’s what put former U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt in a wheelchair. The disease is 99% eradicated worldwide, and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 16 million people have been saved from paralysis because of the vaccine. The U.S. has been polio-free since 1979.

MEASLES

MEASLES

Fever, a runny nose, and a blotchy red rash are common signs of this highly communicable virus. Prior to the vaccine, 3 million kids a year would contract the disease. The WHO estimates that between 2000 and 2015, more than 20 million deaths were prevented thanks to vaccination. Yet about 400 children per day still die from the disease as the goal toward eradicating measles has slowed since 2010, due in part to vaccination reticence.

WHOOPING COUGH

WHOOPING COUGH

Whooping cough gets its common name from the sharp intake of breath after long, painful coughing bouts that can make it very difficult to breathe. That’s what makes whooping cough, aka pertussis, so deadly for infants and small children. But mothers can get vaccinated and pass the immunity on to their children. Cases have dropped dramatically in the U.S. thanks to the vaccine, bringing the number of annual cases down from 200,000 to fewer than 50,000.

Comments

Comments are moderated, so there may be a slight delay. Those that are off-topic or deemed inappropriate may not be posted. Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with an asterisk (*).