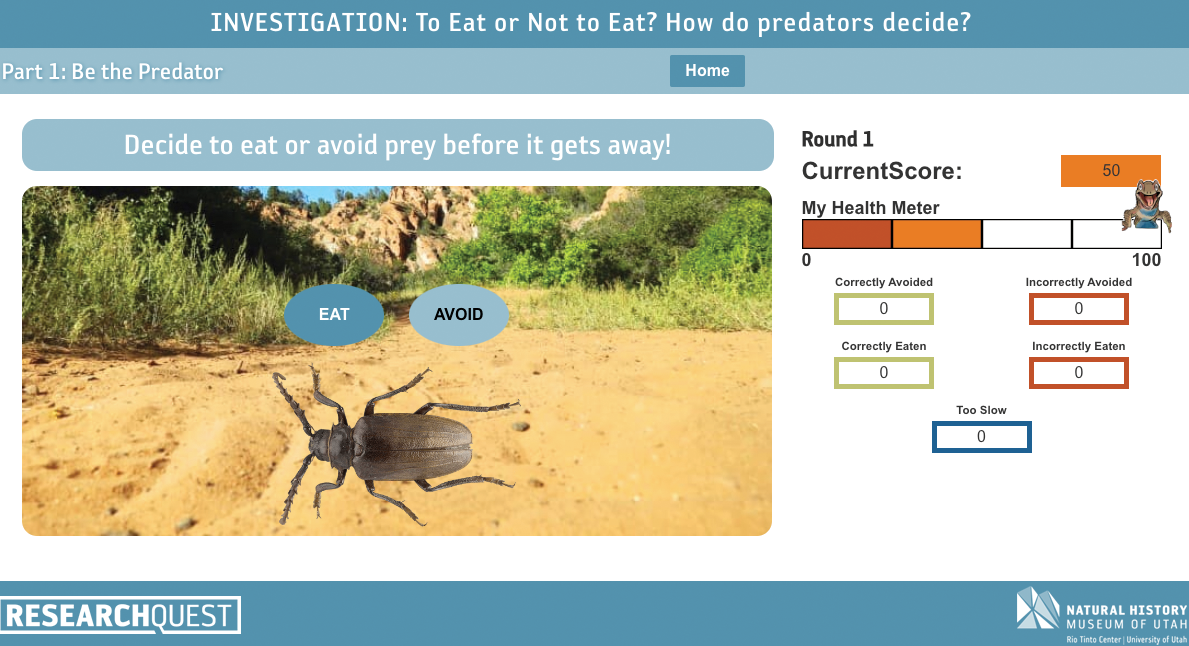

At the back of a sixth-grade classroom, two students are giggling while playing a game called Dino Lab. They’re building a dinosaur by combining different torsos, tails, heads, and limbs and seeing whether their creation can survive a series of challenges—beginning with the ability to stand. Pair scrawny legs with a massive body and the dinosaur will fall apart in a clatter of bones. If you build a sturdy creature, you move on to the next challenge: seeing if it has the right features to defend itself from predators. To the kids, it’s a game. But they’re learning to closely observe and analyze how an animal’s physical traits help it function and succeed in the wild.

Dino Lab is part of Research Quest, a web-based educational program created by the University of Utah’s Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU) that aims to teach kids critical thinking. In the wilds of the digital world, where information overload is a daily threat and fake news can spread like wildfire, critical thinking is the essential skill kids need to separate fact from fiction, make evidence-based decisions, and become well-informed citizens.

An Essential Digital-Age Skill

In 2016, Stanford University researchers asked 170 high schoolers to evaluate a social media post with a picture of strange-looking flowers supposedly near the site of a nuclear power plant disaster. “Not much more to say, this is what happens when flowers get nuclear birth defects,” the post said.

When asked to evaluate the legitimacy of the post’s claims, less than 20 percent of respondents showed what the researchers deemed a mastery of critical thinking skills—like questioning the poster’s credentials or suggesting the image could have been Photoshopped. In the same study, more than 80 percent of middle schoolers believed that an advertisement labeled as sponsored content was actually a news story.

A 2022 Digital Media trends survey from Deloitte showed that about half of Generation Z gets its news from social media. That includes sites like TikTok, where a 2022 NewsGuard investigation found that 1 in 5 videos contained misinformation.

Spreading false claims is nothing new, but social media takes it in “potentially damaging” directions, according to the book Social Engineering by U communications professor Sean Lawson and his York University colleague Robert Gehl. “It shifts from relatively harmless, interpersonal discussions to masspersonal media—especially because Facebook and other corporate social media are built to amplify messages our contacts share with us.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, theories and conjecture seemed to spread on the internet faster than the virus itself. The World Health Organization (WHO) calls this phenomenon an “infodemic”—an overload of information that “can intensify or lengthen outbreaks when people are unsure about what they need to do to protect their health and the health of people around them.”

NHMU’s trove of specimens is the backbone of real-world investigations into scientific mysteries. Butterfly image above: UMNH.ent.0041981, Papilio palinurus daedalus

ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OF UTAH (UMNH) AND THE BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT

7585

Allosaurus fragilis

Dasymutilla scitula

4631

UMNH.ent.0044936, Buprestis aurulenta

ARCH.ED

UMNH.ent.0073987, Melissodes

Allosaurus fragilis

ET626.34

Allosaurus fragilis

Plateumaris flavipes

ARCH.ED

Whether in politics or health care, deep thinking skills can help people make evidence-based decisions. And the usefulness of those skills extends beyond those realms into the workplace as well. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine calls critical and analytical thinking a fundamental skill workers need today. In the age of AI, say employment experts, employees with strong “human” skills like critical thinking will become more in demand.

“Going forward, people will still need to know specific bodies of knowledge to be effective in the workplace,” says Northeastern University President Joseph E. Aoun in his book Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. “But that alone will not be enough when intelligent machines are doing much of the heavy lifting of information.”

In Search of a New Learning Tool

It was concern about kids encountering misinformation on social media that led to the birth of Research Quest. About a decade ago, members of the Rosenblatt family noticed younger kids were joining Facebook, Instagram, and other social platforms. “There was no real approach to teaching them to be critical about the information they were receiving,” says Toby Rosenblatt.

The Rosenblatts—longtime supporters of the U who are dedicated to the field of education—turned to the U to start discussions about helping develop and fund a program that would teach kids critical thinking skills. Toby’s niece, Jody Rosenblatt, suggested they approach the Natural History Museum of Utah.

“Initially, we thought that natural history didn’t sound like a very strong connection,” says Toby. “But she persuaded us to talk to them.”

Jody knew the impact an NHMU educational program could have on young minds. She had participated in the museum’s school programs when she was growing up. As the state’s official natural history museum, part of NHMU’s mission is to promote science education and serve as a resource for K-12 teachers throughout Utah. NHMU hosts field trips, of course, but it also brings the museum to the classroom through initiatives like Museum-on-the-Move—a traveling collection of artifacts. NHMU’s programs made such an impact on Jody Rosenblatt that she fell in love with science. Today, she’s a cell biologist.

After meeting with the Rosenblatts, leaders at NHMU were on board with the idea. They put together a team charged with creating a program that would be accessible to a wide number of teachers and students—in Utah and beyond—and would have measurable impact. The Joseph and Evelyn Rosenblatt Charitable Fund would support research and development of the program.

The team—which included university research scientists, expert teachers, and curriculum developers, along with professionals from the worlds of digital learning, museums, and game design—began with the question, What is critical thinking?

“There isn’t a ubiquitous definition,” says Madlyn Larson, associate director of education initiatives at NHMU and project director for the development of Research Quest. “So we defined discrete skills we wanted to effect: how to make strong observations and inferences, how to engage in analysis, and how to develop arguments based on evidence.”

That requires going beyond the shallow learning of regurgitating facts, says Kirsten Butcher, a professor of educational psychology at the U. “What works best is if we design investigation contexts where learners are challenged to integrate new information with prior knowledge, generate new ideas, and be critical of their assumptions,” she says.

As director of the U’s Instructional Design and Educational Technology Program, Butcher was brought onto the team to help create an engaging web-based program that resulted in meaningful and measurable increases in student knowledge. The team put together prototypes that had students investigating scientific mysteries, incorporating lots of multimedia and interactive games—like Dino Lab—developed by designers in the U's Division of Games (formerly the Entertainment Arts & Engineering program). Data from pre-and post-assessments showed that the students who used the investigations scored significantly better than their control group peers on reasoning with evidence. The successful program was ready to be launched far and wide.

Investigation over Memorization

Back when she went to school, says Rachael Coleman, science was all about memorization. “There were certain students who wanted to be chemists because they loved memorizing the periodic table,” says Coleman, a science specialist at Jordan School District. “But when you get to be a chemist, you realize that’s not really what you’re doing.”

Coleman and her district colleague Lynn Gutzwiller say they focus on teaching kids critical thinking because, simply put, that’s what scientists do. And that’s why they find Research Quest so valuable.

“There is a deep, dark void of online virtual investigations that are free, high quality, and help students access critical thinking and deeper learning skills,” says Gutzwiller. Research Quest strikes the right balance of engaging and educational, she asserts. It aligns with rigorous Next Generation Science Standards, “but it isn’t so collegiate that it’s out of the realm of understanding for a sixth grader.”

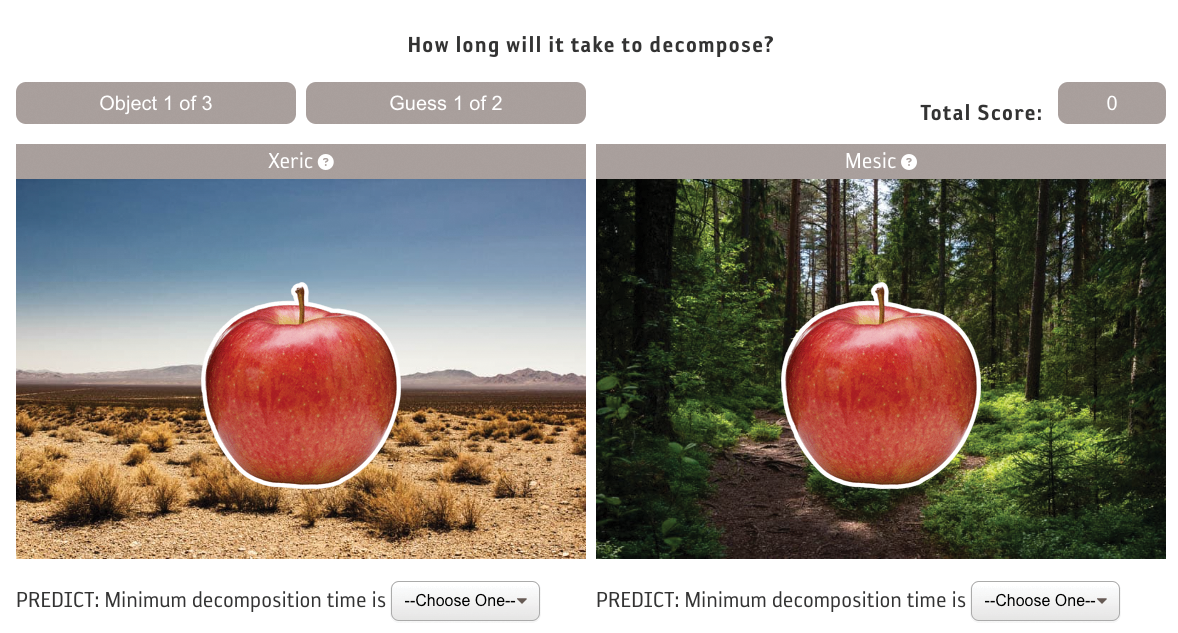

At the heart of every Research Quest module is a real-world scientific mystery. One investigation begins with a video of an NHMU educator in a lodgepole pine forest. Dry branches crack under her feet as she walks through a stand of bare gray trunks. “What is killing all these trees?” she asks. “Something strange is going on.” In another investigation, a paleontologist stands next to fossils discovered at Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry. “I’d like you to develop a hypothesis to answer the question, What dinosaur did these bones come from?” she says.

Each investigation involves a set of virtual activities where students explore digitized museum collections and data to gather their own evidence for the research question at hand. “We give kids the opportunity to collect their own data so they understand where data comes from,” says Larson.

The Cleveland-Lloyd module, for example, has kids studying 3D fossils on the screen, rotating them this way and that for a detailed view. After writing down their observations, students watch the paleontologist explain her own findings.

“It shows students that this is the depth of answer we’re looking for,” Coleman notes. Instead of just saying, “It looks like a claw,” they’re encouraged to ask deeper questions—what, exactly, makes it look like a claw?

“What’s Killing These Trees?” was the first investigation Kris Larsh and his students tried out. “The kids were like, hey, this is really neat,” says Larsh, who teaches middle school science at Stonewall Public Schools in Stonewall, Oklahoma. Larsh found Research Quest while searching Google for a free science resource that wasn’t just another worksheet. The more investigations his students tried, the more Larsh noticed how engrossed they were. “I was trying to get them off their Chromebooks, but they were still playing around with the triceratops.”

What’s more, he says, the kids began to think like scientists.

“I could sit all day and break down the scientific method. But it wasn’t setting in,” says Larsh. “But when they listened to the scientists talk in Research Quest, I knew they were starting to really home in on what the scientific method was.” Their science fair projects became about more than just throwing Mentos into a bottle of Coke and seeing it foam up. “The kids started saying, ‘What if I change the variables?’ That’s when I knew magic had happened.”

Extensive data from the Research Quest team’s studies proves its effectiveness. The team employs several methods, such as listening to student conversations as they work on the investigations.

“That allows us to understand the depth of the processes they’re using to gather evidence and make decisions,” says Butcher. The team uses their observations to keep improving the program, she explains. “One thing we have found as we’ve developed our approach over time is that students are really digging in deeply. They’re using evidence in much more principled and strategic ways than they did before, and they’re realizing one piece of evidence is never sufficient. You need a pattern of evidence.”

“In the earlier iterations, we saw kids latching onto an idea early,” Larson adds. “That ran counter to our desire to create flexible thinking.” After tweaking the modules to increase time spent on data collection, she notes, “students were able to argue with evidence more effectively and stay open to new information as they progressed.”

Gutzwiller says students who want yes or no answers sometimes get frustrated at first, but they learn that it’s okay to take risks as they learn. “They realize, ‘I don’t have to have the ‘right’ answer as long as I can support my answer with evidence,’ ” she says. “I think that’s really powerful. That might be the best thing they take away from Research Quest.”

Amplifying the Impact of Research Quest

Today, Research Quest has been used by more than 1,300 teachers whose students have logged into the investigations more than 400,000 times. The proven effectiveness has earned the program recognition—along with funding from the Utah State Legislature’s Informal Science Education Enhancement program and a $1.3 million grant from the National Science Foundation. In addition, Research Quest receives ongoing philanthropic support from the Joseph and Evelyn Rosenblatt Charitable Fund and the I.J. and Jeanné Wagner Charitable Foundation.

“I think it’s beneficial for NHMU to be able to count on long-term funding for this innovative initiative,” says Toby Rosenblatt.

Larson says an unplanned secondary goal has emerged: to share their framework for how to create an effective digital educational program that leverages natural history collections.

“I’m always mindful that as part of an academic community, we have an obligation to contribute to the creation and dissemination of new knowledge,” she notes. “This, for us, is one important way we can impact critical thinking in young people—by sharing what we’ve learned with others interested in doing similar work.”

Lisa Anderson is associate editor of Utah Magazine.

Critical thinking is so important…as a graduate in Cultural Anthropology from the U of U in 1979 at age 40 and then going into teaching when I completed my BA in Elementary education in 1980…Critical thinking was at the core of many of my methods, from dinosaurs to community development in in 2nd grade, making fossils, books, bringing in science activities into reading enrichment. Shift to 3rd grade and introducing critical thinking to these 8 year olds included taking a strong look at China’s use of children in their productions, breaking them into groups, lots of discussion of China made vs. USA made and their parents’ pocket books…Every year during learning more about Rosa Park and Martin Luther King, showing films of the marches in the south, etc…talking about discrimination. I was thrilled one day when one of the students came running to me during recess, said one of the boys was picking on a girl…and I asked him to point out the girl…he said the “girl in the red and white dress”…It was the only black student we had. That was a winner! I’m 84 now, and still miss those days and opportunities to enrich children’s lives.But, I have grandchildren in the wings!

I graduated from the U and would love to share the critical thinking app/program with my grandchildren – is there a way to do that?

Thanks!

Hi Dave, Absolutely! Visit https://researchquest.org/investigations.php to get started. Best of luck!

You have discovered the digital-age, evolutionary missing link conceptualized in A Wrinkle in Time. Your critical thinking-based approach is the vital link to maintaining the human race’s fitness to survive the inevitable global A.I. tsunami. Only a few standing on the watchtowers have, even imaged the juggernaut, let alone have been able to predict its consequences on human growth, development, learning, and intelligence. (Funny thing;I am relying on Grammarly to check my text and it didn’t catch that I spelled intelligence wrong. I had to have Siri spell it for me, I hate to admit to how many advanced degrees I have.).

I can imagine a digital gap wider than the Grand Canyon eroding civil societies in a just a few months instead of eons of time. There will not be many standing on the advantageous side of the gap unless we align education systems to promote the evolution of critical thinking in line with the digital age. This basic tenant must be instilled in everyone from birth to last breath, that continous brain development and learning makes us human. Hopefully, we learn to thrive not just survive as in the dystopic movies Wall-E or even darker, The Matrix. ( I hope I spelled everything right, Grammarly, wants me to upgrade my dependence on them to a paid subscription so I think it it messing with me.)

In today’s digital age in the face of machine learning let’s turn the tide to create educational forces that are empowered by critical thinking and the capacity to use A.I. wisely and ethically.

Let’s join forces in a state-wide learning quest to prioritize critical thinking at the foundation of all human intelligence.

Always Learning,

Susan Leora Knott

Educational Leadership and Policy Doctoral Candidate

U of Utah