Who would ever think that making fish dance could be so much fun? Johnny Staples loves doing it. The 33-year-old with autism is a great fan of the virtual reality game Choreografish, developed in the U’s Therapeutic Games and Apps Lab, aka The GApp Lab. Choreografish is just one of the many therapeutic and instructive apps and games students and instructors in the lab have created to help children and adults deal with issues like cancer treatment, cognitive impairment, and motor skills development.

Choreografish isn’t a game in the sense of skill, strength, or luck determining a “winner.” Instead, Choreografish helps players tune out the often-overwhelming stimuli of the outside world and create a soothing environment they can control, helping them experience a sense of well-being.

Ready, Player One

Staples dons a virtual reality headset, selects a favorite piece of music to accompany his virtual undersea voyage, and holds the consoles that allow him to manipulate the patterns of fish as they swim through the water, around a sunken ship, or even into an octopus garden.

Afterward, he flashes a smile that could light up the Salt Lake City skyline. “It feels very cool being in control [of how the game plays out],” he says. “Whenever I play it, I feel better. It calms me down.” Staples’ mother, Meg, will never forget the first time he played Choreografish. “When he took the goggles off, his face was pure and complete joy,” she says. “I’d never seen that before. As a parent, that memory still chokes me up.”

“It’s great for people who have special needs,” he adds. “If I had the game, I’d probably play it every day.”

Johnny Staples played Choreografish several times during its development, and after each round, GApp Lab engineers, designers, and students solicited his feedback. His suggestions were often incorporated into the game. And Staples now has another idea: “In the octopus garden, I’d like to see them add a yellow submarine and some Beatles songs.”

Roger Altizer MS’06 PhD’13, director of The GApp Lab, and director of digital medicine in the Center for Medical Innovation, loves the idea. “That would be awesome!” he says with a chuckle.

Quick! Someone call Paul McCartney!

Opening the GApp

Altizer founded The GApp Lab in 2013 after University of Utah Health approached him about developing digital programs to help train health care workers. Altizer, a forward thinker fascinated with the interplay of technology and health care, knows that the future of medical diagnostics includes video game technology.

A 2012 American Journal of Preventive Medicine study found that using video games improved 69% of psychological therapy outcomes, 59% of physical therapy outcomes, 50% of physical activity outcomes, 42% of pain distraction outcomes, and 37% of disease self-management outcomes. That same year saw the launch of Games for Health Journal, a peer-reviewed publication highlighting game research and technology in the health care industry.

In June 2020, the FDA approved the first game-based digital therapeutic, EndeavorRx. Developed by Boston-based Akili Interactive Labs, the video game helps treat children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. FDA support is important because it allows physicians to prescribe the game—just as doctors prescribe approved medications—and makes it possible for insurance companies to cover the cost of games for patients.

EndeavorRx’s success gives hope to Altizer and others in The GApp Lab that the government has begun taking seriously the idea that video games can be used as treatment for some medical conditions.

Briefly, The GApp Lab is a collaboration supported by the U's Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library, Center for Medical Innovation (CMI), Population Health Sciences department, and the College of Engineering's Entertainment Arts and Engineering program (EAE). The EAE program teaches students not only how to design video games, but how to cooperate with others to produce those products. In addition, students learn the business side of game and app production. And the idea for Choreografish grew out of the CMI, which is focused on developing and advancing medical digital technology.

"IT FEELS VERY COOL BEING IN CONTROL. WHENEVER I PLAY THE GAME, I FEEL BETTER. IT CALMS ME DOWN."

The U’s EAE program was rated the world’s No. 1 program of its type in a public university by The Princeton Review in 2020, and so far has generated more than 100 published student projects.

On any given day, The GApp Lab hums with activity as students and their mentors write code and design cutting-edge graphics that colorfully splash across video screens. The thok-thok-thok sounds of fingers hitting keyboards is like a musical soundtrack to all the intellectual creation.

Altizer says he started GApp because “I really want to make a difference in people’s lives using digital medicine.” And to those who question whether therapeutic video games have a place in the health care industry, he answers with a shrug, “In life, we all work too hard, and when medicine looks too much like work, people lose interest in it. I want to make health care playful again. When you ask patients when they were healthiest or happiest, it’s those moments when they’re at play, not at work.”

But that doesn’t mean he’s all work and no PlayStation. “It’s okay to shoot zombies and aliens once in awhile,” he says with a laugh, referring to students whose goals are creating games worthy of inclusion in an Xbox console. “I spend half my day working on EAE students’ games, and the other half on playful digital medicine at U of U Health.”

Controlling Reality

Eric Handman MFA’03, associate professor of modern dance, envisioned a video game played on a tablet that would help people on the autism spectrum develop an appreciation for dance. His idea: players would use music to create movement patterns among flocks of birds.

“I was intrigued with the idea of how pattern thinking was important both in dance and in those with autism,” he says. “Dance is a social art form, and I wondered how people on the spectrum could access choreography on their own, without the social stress of being in an audience with other people.”

He took his idea to Altizer; Cheryl Wright, professor of family and consumer studies; and Greg Bayles MA’16, a GApp Lab project manager. Altizer proposed changing the graphics to schools of fish, as research showed water was more calming to people with autism. In addition, the game went from being screened on a tablet to played with a virtual reality headset so users could tune out the outside world and create their own peaceful inner sanctum.

Bayles says feedback from players like Johnny Staples helped improve Choreografish. “What the users were most struck by was their ability to control the scene,” Bayles says. “They wanted to stay longer and explore the environments we created. They liked being right in the middle of the fish as they virtually swam around the player.”

The Gapp Lab unveiled Choreografish at the Sundance Film Festival in 2017, and “we got a marvelous response,” Altizer says. The game is currently looking for venture capital to help bring it to market, “but if that doesn’t happen, we might just put it on the Internet for people to download,” he says.

Empowering with Play

An 8-year-old boy fighting brain cancer inspired Grzegorz Bulaj, associate professor of medicinal chemistry, to create a video game to empower the youngster’s mind against his illness. “The boy, a nephew of my friend, enjoyed playing the prototype game,” Bulaj remembers. “Later, I thought, ‘What if we could create a therapeutic game to help children undergoing chemotherapy become mentally and physically stronger?’ ”

Collaborating with U pediatrician Carol Bruggers, The GApp Lab, and Spy Hop (a local nonprofit youth media organization), Bulaj’s idea morphed into Empower Stars, a mobile game where kids can imagine themselves as superheroes on a mission to restore a barren planet while overcoming various challenges. The game is played on an iPad with motion sensors that detect hand movements, and daily rounds last for 30 minutes—long enough for children to get some mental and physical exercise but not to tire them out.

THE THOK-THOK-THOK SOUNDS OF FINGERS HITTING KEYBOARDS IS LIKE A MUSICAL SOUNDTRACK TO ALL THE INTELLECTUAL CREATION.

The game has its roots in the concept of patient empowerment, where players feel they can learn to control situations that may seem overwhelming, mirroring the serious illnesses they’re dealing with.

Empower Stars was clinically tested by children with cancer, their parents, and health care providers. Bruggers and Bulaj hope to secure funding for further development, and ultimately to gain FDA approval of Empower Stars for pediatric oncology patients.

Nursing professor Lauri Linder BSN’89 MS’94 PhD’09 and The GApp Lab are developing another game for children facing tough medical issues. Because youngsters often are hesitant to talk about their illnesses with doctors, The GApp Lab introduced Color Me Healthy, where children describe the sensations and symptoms they feel in their bodies by coloring pieces of an avatar’s body displayed on a tablet.

Bayles is excited by the interest generated by Color Me Healthy, which has received a number of grants from the National Institutes of Health and St. Baldrick’s Foundation. “Our research shows the app has generated 40 percent more conditions and symptoms than just talking to the doctor,” Bayles says. “Children see it as a fun and cool way to generate a report for clinicians.”

Recharging the Brain

When Scott Gutting was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, he became depressed, fearful that he was on a slow slide toward more serious cognitive decline.

“After the diagnosis, the doctor basically sent me home saying there was nothing he could do to help me,” Gutting remembers. “Well, no one was going to tell me that at my age I couldn’t do anything to help myself. I decided to find some type of cognitive remediation.”

His daughter, a professor at Columbia University, told him about studies of remediation in older adults—using specially created video games—conducted at the U by Sarah Shizuko Morimoto, an associate professor of population health sciences. For more than a decade, Morimoto has designed video games that rejuvenate damaged circuits in the frontal lobe that seem to block the effectiveness of antidepressant medication. The brain games appear to improve cognitive functions while decreasing players’ disability.

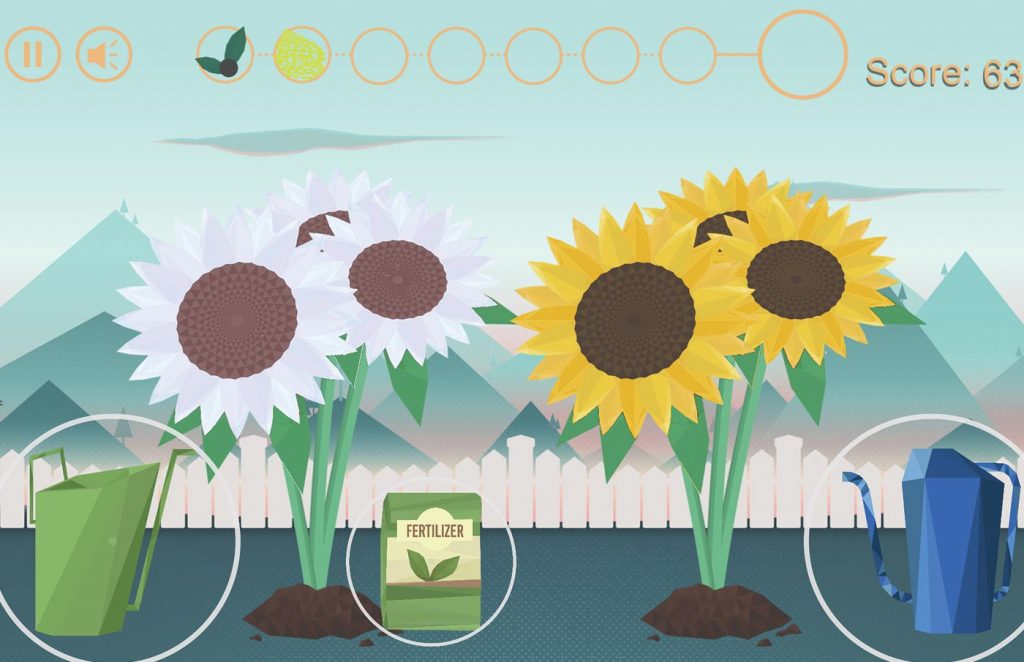

With The GApp Lab, Morimoto created Neurogrow, which involves planting and tending a virtual flower garden with actions like watering, fertilizing, and eliminating pesky bugs. Players get points for cultivating bouquets, which they can then award to friends, and move on to more complicated levels and garden plots.

“Neurogrow has a deeper, double meaning,” Morimoto says. “Tending a garden is like tending to your aging brain. To stay healthy, your brain needs attention and care.”'

In their first clinical trial, Morimoto's team found that four weeks of Neurogrow provided relief for 60%-70% of patients who hadn’t previously responded to antidepressant medication. In a subsequent clinical trial testing Neurogrow against another mentally stimulating computer program, 60%-70% of patients reported a 50% reduction in depressive symptoms.

“The game creates hope in patients, which is incredibly important for them to improve their mental abilities in the face of cognitive decline,” she says. “We’ve optimized the game for seniors because aging brains react differently to medication than younger brains. Plus, using the game is a way to treat vulnerable people at home cost-effectively with evidence-based medicine.”

Like Empower Stars, Neurogrow is undergoing clinical trials to prove its efficacy.

Gutting finds Neurogrow fun yet challenging. “Sometimes I get mad at the machine,” he says with a chuckle. “The game really works my brain, but I do see a definite improvement. In fact, I find that when I take a week or two off, I miss it and my memory functions aren’t as sharp.”

Though Gutting’s wife, Lesley Jones, isn’t dealing with cognitive impairment issues, she plays the game, too. “Why wouldn’t I do this?” she asks. “I want my brain to stay young.”

Keeping people mentally and physically fit is what The GApp Lab is all about, says Altizer, who takes pride in the people around him and the games they produce. “I work with so many talented people: artists, doctors, engineers, programmers, patients, and clinicians. And when I see how the games are helping people—that’s an awesome, wonderful feeling.”

About the author: Benjamin Gleisser is a Toronto-based freelancer.

House of Games

More than three dozen games and apps sure to significantly impact the way students will learn in their disciplines are in various stages of development in The GApp Lab. Here are just a few recent creations:

It’s said that George Clooney knew nothing about hospitals when he began working on the TV show ER. Too bad he didn’t have TraumaXR, which creates a virtual operating room for training surgeons and nurses. The app can also be used to prepare health care workers at rural or smaller urban hospitals for emergencies they may one day encounter.

Athletes with serious spinal cord injuries no longer have to leave the sports they enjoy. TetraSail is a game simulation jointly developed by the lab and the U's TRAILS program to provide systems that help tetraplegic individuals (those who are unable to move their upper and lower bodies) learn to control a modified water vessel by using a joystick and/or sip-and-puff controls. Similarly, TetraSki helps users master an alpine sit-ski chair. The goal of both games is to prepare players to get out on the open sea or onto the slopes.

What should a newly hired social worker look for when making an in-house inspection to check on the welfare of a child? Is a messy room always a red flag? To answer those questions, social worker Chad McDonald MSW’12 reached out to The GApp Lab to develop Virtual Home Sim, a game overseen by Jesse Ferraro MFA’13 that presents an array of virtual house interiors with embedded clues for social workers to remember when making real in-house visits.

To see more fascinating games developed in The GApp Lab, visit games.utah.edu/research/sampleprojects/

I host a video podcast, The Wide World Of ESports on the ThinkTech Hawai’i live-streaming network. If anyone at the U who’s working on application of games would like to be a guest on my show, please email me.

Fallout 4 and Skyrim SE are excellent for Senior Citizens.