DATA SCIENTIST MIKE MARTINEAU doesn’t use a crystal ball to predict if a freshman will graduate in six years or less. His not-so-secret method for foretelling student success? Has the student (1) completed math and writing during first year, (2) met with an academic advisor to identify and declare a major as soon as possible, (3) stayed in school full time, (4) found a “sticking point” on campus (faculty mentor, work study, internship, etc.), and (5) met with a financial aid counselor to come up with a plan to pay for college.

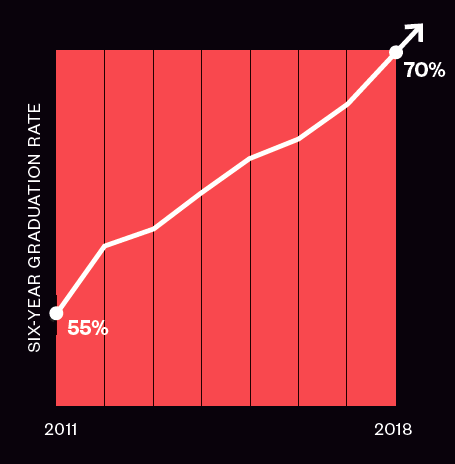

But Martineau BA’08 MS’12 PhD’13 and his team in the Office of Institutional Analysis are doing a lot more than just predicting a student’s likelihood to graduate. They’re using real-time data to identify students who might need extra support along the way. And this approach has produced some extraordinary results. Most notably, the six-year graduation rate has skyrocketed from 55 percent to 70 percent since 2011. The U is just one of two research universities in the country to see such a jump. “Improvement like this is truly outstanding,” says Martineau. “It puts us at the forefront of a national movement.”

Martineau credits a meeting he had with then-provost Ruth Watkins as one of the driving forces for the change. After reviewing the data his office had been collecting, she challenged them to use it for meaningful and systematic change—to help more students graduate and do it more efficiently. “Her mantra has always been that access to college without completion is a hollow promise,” he says.

What followed was a fundamental cultural shift in how the U views big data—from reactive to proactive. Martineau puts it this way: “When it comes to decision making, we’ve gone from looking in the rearview mirror to seeing out the front windshield.”

"Access to college without completion is a hollow promise."

advising

A NEW APPROACH

It’s a daunting challenge. To take vast amounts of data and serve up actionable insights for advisors was a complete shift of perspective, says Martha Bradley BFA’74 PhD’87, dean of undergraduate studies. “We needed a new, more analytics informed approach to student advising,” she says.

First, they identified institutional roadblocks that could slow graduation. For instance, they could see which courses were filling up fastest and creating registration bottlenecks, so they added more of those sections,

including online. The data also pointed to the value of academic advisors— who help students not only identify and declare a major and but also chart a personal course to graduation. In response to the data, the U expanded its number of advisors and key advisory milestones: before students register for the first time, before their second semester, and during their sophomore year.

Next, the data helped Martineau’s team identify student behaviors that might indicate a risk for not persisting— using what they call dashboards. Connecting to the university’s robust data sets, these dashboards congregate and visualize data to show overall trends, and even drill down to the individual student level. They track more than 200 indicators, such as when students register for classes and how often they log into the online learning system compared to their classmates.

But what makes these dashboards so powerful is their ability to distill hundreds of indicators from tens of thousands of students and serve up the most important and actionable information. “Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach to advising, we can say, ‘These are the students who need us right now,’ ” says Beth Howard, associate dean of the Academic Advising Center. All of this information is a way to start conversations and will never replace human interaction, adds Amy Bergerson PhD’02, associate dean for undergraduate studies. “It’s a way to aid responsible human decision making—never a substitute.”

input

DATA-DRIVEN DECISIONS

1. No appointment? No problem. Started an open-door policy for financial aid counseling.

2. Removed common obstacles that can delay graduation—not getting into required courses, running out of money, poor planning, etc.

3. Formed a “strike-force team” to swoop in, meet students where they are, and help connect them to campus resources.

4. Launched a one-stop shop for scholarships. Gone are the days of hunting around campus and filling out heaps of applications.

5. Hired more academic advisors—upping the student-to-advisor ratio by 20%. And, the U expanded mandatory advising for all students.

6. S.O.S. Advisors can now use real-time data to find students who need help before their grades slip or they drop out.

7. No procrastinating: advisors emphasize math & writing for all freshman. Data shows they’ll have better academic success if they don’t wait.

8. Location, location, location! Students who live on campus are more likely to graduate quicker. It’s one reason why the U is investing in new housing!

9. A home away from home. The U is helping students make stronger connections with faculty mentors and find jobs on campus.

nudges

BEFORE IT’S TOO LATE

Timing is of the essence. Rather than reaching out at the end of a semester, when a student may have already failed or dropped out, advisors can now offer support sooner to those who are missing class or whose grades drop dramatically over the course of the class. They do this through email “nudges.” Since 2011, a whopping 65,000-plus nudges have been sent to students. “These nudges communicate everything from friendly reminders that it’s time to register for the next semester, to direct messages encouraging students to reach out if they need additional support,” says Howard.

And when a student needs support beyond academic planning, the U’s Student Success Advocates (SSAs) step in. Think of this team as a “strike force” of front-line advocates for students. They don’t have offices; instead they’re out and about on campus helping connect students with resources such as scholarships and job opportunities, and even during food or housing crises. And the SSAs stay executive director of the Office of Scholarships and Financial Aid.

“Students’ first concern shouldn’t be how they’re going to pay for school,” she says. “They should be able to focus oncoming to school, going to classes, and getting the education and experience they need to go out and be successful after they graduate. And they should busy. They’ve interacted with upwards of 9,000 students more than 30,000 times.

When Oliver Perez received a nudge from the SSAs his freshman year, he asked for help. The first-generation student studying the philosophy of science says that text changed the course of his education. His advocate, Christine Contestable PhD’10, met with him that very day and listened to his concerns. She walked with him to the financial aid office to meet with a counselor. They still text regularly and meet about once a month. “I didn’t know much about the basics when it comes to college,” says Perez. “I honestly don’t know how I’d do school without her.”

financial aid

SHOW ME THE MONEY

It doesn’t take big data to know that if students run out of tuition money, their degree is at risk—no matter how many nudges they get or when they take math. That’s why the U is expanding its focus and offering additional resources to help students cover the cost of attending school, says Brenda Burke, executive director of the Office of Scholarships and Financial Aid.

“Students’ first concern shouldn’t be how they’re going to pay for school,” she says. “They should be able to focus on coming to school, going to classes, and getting the education and experience they need to go out and be successful after they graduate. And they should have access to a variety of financial aid resources when determining how to cover the cost of college.”

Burke has helped oversee a staggering increase in scholarship and federal funding going directly to students. Much like how the U views big data, these improvements came from changing culture, she says. More outreach was key, which led her office to having a new outreach coordinator, who will coordinate more than 50 financial aid and scholarship workshops around campus and the surrounding community this year alone.

In addition to going out to the community, financial counselors are making themselves more available than ever. Before, students had to make an appointment—sometimes weeks or even months out.But now, the office has an open-door policy, which has made a huge difference. Annual visits to the counselors have increased from 400 to more than 7,000 over the past few years.

One of the first steps to receiving financial aid and need-based scholarships is to fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form, which provides guidance on what types of grants, scholarships, loans, and work study options are available to students. The state of Utah has the second-lowest completion rate of the FAFSA form in the nation; just 38 percent of students fill it out, leaving an estimated $40 million of potential grants on the table. Since the open-door policy went into effect at the U, total FAFSA completion has improved by nearly 30 percent, and total financial aid dollars awarded increased by nearly 20 percent.

But students don’t have to physically go to the office to benefit from the improvements. Now, the U has a new scholarship database that consolidates most department and college scholarships into one central online location. Instead of searching the web for hours, students can fill out one application, along with interests, background, etc., and they are notified by email when new opportunities open. All these efforts are having an enormous impact. Over the last five years, scholarship dollars awarded at the U have shot up by an astounding 93 percent.

“These are the students who need us right now.”

investing

THE FINAL STRETCH

But data shows that easier access to scholarships and other financial aid isn’t enough for all students, particularly for juniors and seniors. After federal aid and scholarships come through, many students still struggle to pay for those last few semesters. To compensate, they work more, take fewer credits, and delay graduation. And that’s where an income share agreement, a new financial aid option, was born.

In its first year, the Invest in U program lets seniors in selected majors get up to $10,000. But instead of paying interest as with a traditional loan, students will pay 2.85 percent of their monthly income over a three- to 10-year period, depending on the amount and major, says Courtney McBeth, who oversees the program. And payments will go back into Invest in U, creating a perpetual fund to help future students. “We haven’t seen a new financial tool in decades, until now,” says McBeth BA’01 MS’05. “We’re contacted by at least a dozen other universities, media, and national groups a week who want to learn more.”

Invest in U is a statement of confidence for the U, says Martineau. “It makes us put our money where our mouth is,” he says. “We’re so sure that if you get a degree from us that you’ll be able to get a well-paying job that we’re willing to put the money up front.”

All these resources are leading to better graduation rates, more financial aid, and less student debt. In fact, fewer than half of undergraduates (40 percent) from the U graduate with any student debt at all. That’s the best percentage of any public institution in the state.

goals

WHAT COMES NEXT

Not the types to rest on their laurels, Bradley, Bergerson, Burke, Howard, Martineau, and their teams are already setting an ambitious new goal—to take the six-year graduation rate even higher, up to 84 percent. So how do they keep building on nearly unprecedented growth? They use big data, of course.

For example, they now know that students who live on campus are 12 percent more likely to graduate in six years or less, so more dorms are being built. And to help students find those “sticking points,” the U is growing its campus workforce and putting renewed emphasis on internships and workstudy programs. And the Invest in U initiative is slated to roll out on a much larger scale. They’re also working on getting more data in the hands of faculty And, while Utah Magazine was at press, the U hosted a national College Completion Summit, in partnership with Lumina Foundation, that brought together leaders from public universities around the country to share best practices for increasing college completion rates, showing the U as a leader in using data and innovation to help more students graduate.

It’s not just a single lever that makes a difference. Whether it’s improving access to financial aid, sending nudges, or hiring more academic advisors, the U is committed to helping students reach their highest potential and get a meaningful return on their investment, says Bradley. “Understanding data helps us develop individualized approaches. It’s a guide, not the solution.”

GETTING TO GRADUATION

Only two public Research I institutions in the U.S. have increased the graduation rate by at least 19 percentage points in the last decade—and the U is one of them.

WHY SIX YEARS

Why focus so much on graduation rates? Shouldn’t students study as long as they’d like? Well, na-tionally, one in three students who start college will never get a degree, and more than half don’t finish in six years. And that’s only compounded for lower-income students and those from other underserved populations.

As students stay in school longer, they rack up more debt and lose out on earning potential. Each year a student stays in school can cost $70,000 in expenses and lost income potential, according to a study by Complete College America.

Martineau points out that the benefit of a de-gree versus just some college is immense. “A university degree is still the best signaling mech-anism to employers that someone can meet deadlines, work collaboratively, complete objec-tives, and think critically.” So why is six years the magic number? In 1990, Congress passed the Student Right-to-Know Act that required colleges to disclose six-year grad-uation rates, which is equal to 150 percent of the normal completion time of a bachelor’s degree.

This has become the national reporting bench-mark for colleges and universities to compare. And for those wondering about U students who take a two-year sabbatical for religious reasons—that is accounted for in the graduation rate.

output

DATA-DRIVEN OUTCOMES

1. Always welcome. Annual visits to the financial aid office jumped from 400 to 7,000, and financial aid increased by 20%.

2. Smoother sailing. The U added new sections of required courses, more online offerings, and inventive ways to pay for school.

3. Staying in touch: Student Success Advocates have interacted with 9,000 students a total of more than 30,000 times.

4. Congratulations! Scholarship dollars to students has increased 93% in the last five years.

5. I do declare. Four out of five first-year students have declared a major, up 12% in the last five years.

6. Before it’s too late: 65,000+ data-inspired nudges sent to students who might need extra support, most before the end of the semester.

7. Fewer cases of “math atrophy” as 78% of students now take their arithmetic requirement within their first year.

8. Vacancies ahead. New on-campus housing to open fall 2020 with 990+ new beds, bringing the total to more than 5,000.

9. Now hiring! The U is growing its student workforce: 24% of undergrads now hold an on-campus job.

About the authors: Christopher Nelson BA’96 MPA’16 is the U's communications director. Seth Bracken is the managing editor of University of Utah Magazine.

Really great article! I’m so glad the U is doing so much work to help the students who need it most.

I love it! I wish I had a Student Success Advisor when I was going to school. Probably wouldn’t have taken me so long to graduate. Go Utes!

Huh. You hear so much about the negative aspects of big data. Interesting to see how it’s being used beyond just tracking our online presence. Normally, I’d say get big data out of pretty much everything. But in this case it seems to be helping students, so I guess I’m on board. Fascinating approach.

It’s great to see the graduation rate increasing. During orientation before my first semester at the University of Utah, the “advisors” told the incoming group that they would be overwhelmed if they took more than six credits per semester. Martineau’s data shows that this was a crucial mistake that did not maintain full time enrollment. With cultural pressure to support a family, it’s especially crucial to ensure that degrees get completed.